003. Optimization

The first two editions of The Tech Leader Docs covered two important pillars of leadership: Communication and Prioritization. (They're available in the Archive if you're new here — and welcome!)

This edition covers an often misunderstood, sometimes vilified, but altogether necessary third pillar.

Optimization is a delicate balance. It's very easy as a leader to under or over-optimize your processes. Developing the skill of knowing how much to do, and when, is vital to your team's success. I'll teach you what to look out for and how to keep yourself in check.

First, Awareness

How do you know when to optimize?

Two concepts are helpful here: your Inner Inefficiency Detector (IID), and a simple cost-benefit formula.

Develop Your IID

A well-tuned IID can make the difference between a decent leader and a great leader. Make a habit of stepping back and re-evaluating processes and decisions. Ask yourself:

Is it better now than it was before?

Does the team feel this is overly complicated? If so, why?

Is there a simpler or faster solution, and if so, why are we not considering it? What's the most naïve solution?

Is this plan going to be maintainable?

It takes some practice at introspection to discover inefficiencies. Make this a routine step in your cycle. Before long it becomes much easier to steer your team away from wasted time and effort.

Some typical things that set off my IID are:

New tools are proposed that don't add necessary functionality

More time is spent categorizing or sorting information than utilizing it

Overblown solutions are proposed to account for use cases that may never exist, or that the customer hasn't asked for

What would you add to this list?

Cost and Benefit

Keep in mind that the ability to optimize doesn't always mean it's a good idea.

Only optimize when the potential gains are positive and worthwhile. For example, you may consider overhauling a process that currently takes two weeks to run. If this process needs to run every month for a year, it currently takes 24 weeks (2x12).

What is the maximum amount of time you're willing to have your team spend in order to optimize this process? Consider both the cost (time and money) spent overhauling the system as well as the amount of time the improved process will still require.

If you spend four weeks creating improvements and get the process down to one week, you've spent four weeks to save 12 weeks over the next year. The time spent on optimization should also be considered, so in this example, your improvement is from 24 weeks to 16, saving 8 weeks.

Run the cost-benefit calculations for your situation before jumping into optimization to help decide if the process would be worthwhile.

Second, OODA

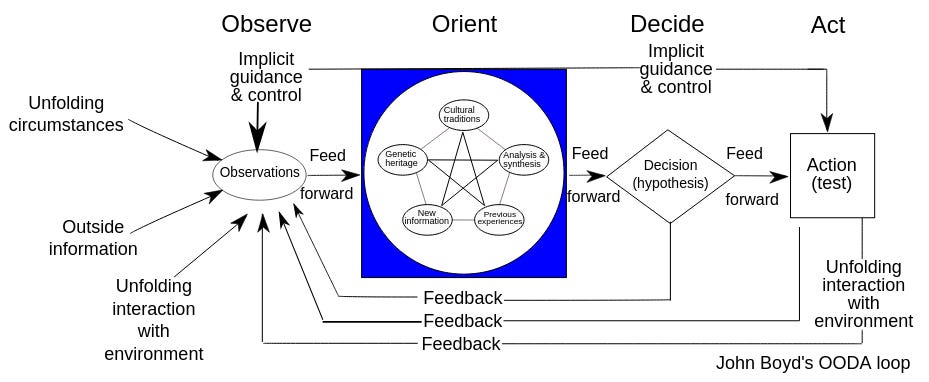

The OODA Loop is a vital concept any leader should be familiar with. The steps Observe, Orient, Decide, Act lay the foundation for you to make informed and relevant leadership decisions.

Here's how the OODA framework applies to anything you want to optimize.

Observe

Gather real information about the thing you want to optimize. A pitfall of many (especially technology) leaders is the desire to solve problems that aren't actually there.

This is often a rationalization to use a Shiny New Technology or to be able to boast some new groundbreaking effort.

Do you have metrics, first-hand accounts (talk with your engineers!), or (internal or external) customer stories that support what you want to see optimized? Are you certain you understand the root cause of the problem, and have you spoken directly with the people experiencing it?

If there's anything you can measure to judge your own success, measure it. This is helpful for determining whether what you're doing is working, for communicating goals to your team, and for summarizing efforts for executive leaders.

Orient

Part of the duties of a leader is to make "good" decisions with the information at hand. What makes a decision "good"?

In the Orient stage, you hone your leadership abilities. The information you gathered can be cross-referenced, analyzed, and synthesized with other information. Your previous experiences, along with insight into different parts of the organization and the goals of its different groups, will combine to help you make the best decision you can with the information you have.

By placing your new information within the full context of what you know, you orient yourself in order to make a "good" decision.

Decide

No decision has a 100% chance of working out the way you hoped. As a (good) leader, you take responsibility for whichever way it goes. It can be helpful then to view each decision you make as a bet.

Bets are probabilistic. There's some chance that everything you planned will work, and there's some chance it won't. Your goal is to use the output of the previous orientation stage to make a bet that is likely, but not guaranteed, to work out.

Considering decisions in this light can help to take the pressure off and put the next stage in perspective.

Act

Once your decision is made, don't hesitate to act. Provide guidance to your team for enacting your decisions right away (don't forget what you learned in 001!).

Indecisive leaders may backtrack or even try to return to the observation stage for more information before putting a plan into action. This is damaging to your cycle time as well as your team's impression of your capability and confidence.

Rather than falling into the trap of thinking that you're committing to this action forever, view this stage as a new testing phase. Putting plans into action is the only way you can learn if they are steering you in a positive direction.

Recall that this is the OODA Loop. By taking action at this last stage, you fulfill the prerequisites for the first. Action begets results that you can further observe and learn from.

Take it to work today:

Practice introspection to better spot inefficiencies in your processes.

Decide if the cost of optimizing is worthwhile.

Use the OODA Loop framework to iteratively optimize anything.